March 26, 1944. A Sunday in Lent. The sun is setting down on the thin line of the horizon dividing the dark sea from the silver blue sky. There is a small piazza in the town of Ameglia and under the tower of the castle, ablaze with the rays of the setting sun, a handful of kids is kicking a ball, their favorite weekend pastime. And as usual, off-duty German soldiers based in the nearby Villa Angelo stroll by in dribs and drabs, and play a ball game with the kids. Athletic vigorvs clever dynamism. The Italian children win the match. The young Nazis, as if making up for the loss, start explaining, through gestures, that they had defeated fifteen Italian-American soldiers that morning. “Kaputt”, they boast, miming the shooting gesture and pointing to the woods of Punta Bianca, between the town and the other sea side.

The kids understand that they weren’t talking about a soccer match. One boy runs to the parish priest and tells him what he heard. The priest reaches out to the American [how about explaining: the American unit based there, or something]and gives them the bits and pieces of information. A network of contacts and relations was in operation, spun by common people fighting their war against Nazi-fascism alongside the Partisans. There are several priests in the network. Such as the one in Ameglia and don Nilo Greco, the vice-parish priest of nearby Sarzana who eventually was arrested and deported.

The story that begun with a ball game in a piazza eventually became part of the official military history. But only today we are able to give accounts of its human implications and provide the biographies of the fifteen young heroes whose names are engraved on a plaque in a hamlet nestled between the sea and the mountains of Liguria.

This is the story of a handful of youngsters who, like other hundreds of thousands over 70 years ago said goodbye to their families from every corner of the world and came to Europe to fight the war that made all of us free. On the spur of the moment, no ifs, ands or buts, they forwent the God-given right to the carefree routine of their young age. It was the thing to do. They did this at the age of our children, who today, thanks to them, can study, play, work, hope without having nightmares that there may not be a tomorrow for them, huddled in a trench, on a ship or an airplane, in an endless desert.

Joseph Libardi

Fifteen Heroes

All of the fifteen American soldiers have Italian last names: Calcara, Leone, Mauro, De Flumeri, Di Sclafani, Noia, Tremonte, Traficante, Vieceli, Squatrito, Russo, Savino, Sirico, Libardi, except one: Farrell, but he too is of Italian origin. It is not a coincidence: one of the policies of the OSS (Office of Strategic Services) is to enlist bilingual personnel to facilitate missions behind enemy lines on the various fronts. This was not an inflexible rule, as John Leone’s now elderly brother recently told us, “John did not speak a word of Italian…”.

Mario Forte, an OSS Veteran recalls that when Italy declared war to the United States, he was an infantryman in Fort Jackson, South Carolina. “They did a roll call and deployed those of us who had Italian last names”.

Joe Genco, another Veteran, explains that afterhe was selected, no one actually asked him whether he could speak Italian. Quite naïf were also the tests designed to determine the candidates’ self-control and aptitude: “Once, I was even asked if I ever had sex with my sister. They were testing our anger. With lesser self control, I would have punched him right on the nose…” says Frank Zabatta, who fought in Italy in the OSS ranks.

October 12, 1944. Upon accepting the Four Freedoms Award presented to him by the Italian-American Labor Council, President Roosevelt said: “The American Army–including thousands of Americans of Italian descent–entered Italy not as conquerors, but as liberators. Their objective is military, not political. When that military objective is accomplished–and much of it has not yet been accomplished–the Italian people will be free to work out their own destiny, under a government of their own choosing”.

OSS is the precursors of CIA (Central Intelligence Agency): it was created in 1942 during WWII with the purpose of coordinating the espionage activities that were carried out separately by the various departments and individual corps (US Army, US Navy, etc.). However, this super-partes role was never actually performed by the OSS, since the FBI (Federal Bureau of Investigation) continued to carry out homeland security and counterintelligenceoperations, while the Army and the Navy lead the relevant intelligence activities. In other words, jealousy and self interestundermined the original idea that President Roosevelt had assigned to General William Joseph Donovan.

A memorable example occurred in1929: Secretary of State Henry Stimson explained why he shut down the State Department’s cryptanalytic office: “Gentlemen don’t read each other’s mail”. Before President Truman signed an executive order terminating the OSS in 1945, the Office was responsible for gathering and analyzing strategic information, carrying out sabotage missions behind enemy lines, supporting partisan and anti-Nazi propaganda groups in Europe, and training anti-Japanese guerrilla in Asia. Often, these missions proved instrumental for the outcome of the conflict, but in many occasionsthey resulted in devastating failure. Grotesque episodes occurred too, like the plan to create a pathogenic goat excrement that would spread anthrax along the enemy lines by means of flies or to introduce estrogen in Adolf Hitler’s meals.

In view of the allied landing in Europe, the OSS and British SOE (Special Operations Executive) received instructions from the Allied Forces Headquarters to organize commando-like missions to urge the Italian people to create resistance groups; sabotage both the communications and the transportation systems in occupied Italy, destroy enemy aircrafts parked in the airfields, destroy enemy refueling depots. Part one of those instructions will trigger the incident that involved the fifteen Italian Americans.

Operation Ginny

Between 1943 and 1944, the “fifteen” men of the 2677° Headquarters Company, Detachment C, Unit A are in Corsica which, having been liberated from the Germans, had been swarmed by a huge number of Allied forces and made into their headquarters. The Allies referred to it as USS Corsica, an unsinkable aircraft carrier.

It is from here that extra hazardous espionage and sabotage operations set out (including the reconnaissance flight in which Antoine de Saint Exupéry – the author of “The Little Prince”-disappeared). One of these is operation code name Ginny: the purpose of the mission is to blow up a railroad tunnel on the Genoa-Pisa line, in Framura, to interrupt communications between Germany and the German Army that in that period was fighting on the Gustav Line. The first attempt (Ginny I) fails the night between February 27 and 28, 1944 because the commando ends up landing far from the target point on the coast of Liguria. The mission was cancelled and the unit returnedto base.

Another attempt is planned for the following month. All the fifteen Italian Americans die. Some of them had been part of the first Ginny mission. Commanding both operations Ginny I and II is another Italian American by the name of Albert R. Materazzi. Born in Hershey, Pennsylvania, he was originally from Montemerano (Grosseto, Tuscany). Albert graduated in Chemistry in 1935 and was granted a scholarship in 1937 which brought him to the Rome University, where he had a direct experience of what Italy was like during fascist dictatorship: “When I joined the OSS I thought I might end up killing my cousins. but I also thought I might be liberating them”.

Stories of immigration

Two of the “fifteen” were born in Italy: Santoro Calcara and Angelo Sirico. One was 17, the other was a baby and after two weeks on board of a ship they landed on Ellis Island, the “gate of hope” through which millions of immigrants transited during at least half of the “Short Century”. Film director Frank Capra, born in Sicily and emigrated to the United States when he was six years old, returned to Italy during WWII. Referring to his trip to America as a kid he would say that was his “moment of origin”: his memories start from there; no memories before the ones on board the big ship. “I thought it was my job to tell our soldiers what purpose the war was. They were 18 years old, knew nothing of the war, had no military discipline. When the war started they were the worst soldiers, but two years later they became the best in the world. The reason is because they were open-minded. The first thing they did was watch my movies. After they saw them they knew what to do, they knew why they were fighting.

In a picture that we were able to find in our work as “paleontologists” of memories, Santoro Calcara, service N. 336131251, looks very proud in his uniform full of pockets. That postcard was sent to his girlfriend Carmela and he penned in the word “me”. Santoro was born in 1920 in Sicily, in Mazara del Vallo, a town of fishermen, who are still fishing swordfish and tuna fish to this day. For his parents, Giuseppe and Rosa, their baby was the sole joyful light of their tough life of unemployment, struggle and the devastating Spanish flu that between 1918 and 1920 cut down almost half a million lives in Italy alone. All they can do is follow the desperate route taken by so many from Southern Italy: one day in July, Giuseppe, with his 5’3″frame boards the “Patria” from the Palermo harbor directed to New York. In tears and with their baby in her arms, Rosa waves goodbye from the pier.

Giuseppe settles in Boston then moves to Detroit where he finds a job and a place to stay, at 2675 Scott Street, sharing the apartment with other twenty immigrants, while Rosa raises Santoro by herself. At the age of eighteen Santoro will follow in his father’s footsteps and emigrate, he too on a day in July, aboard the “Conte di Savoia”. He joins his father in Detroit where the community from Mazara is quite large and where he can reestablish relationships he had in Sicily: Santoro finds his childhood friendsand happily, his sweetheart Carmela, whom he had met in the baroque alleys of Mazara. A picture, with hand-painted retouching shows teenage Carmela in her yellow outfit posing next to her mother. Santoro attends Cass Technical School for two years, he becomes an American citizen and finds a job as a machinist. He dreams of his marriage with Carmela who is now working in a dress factory. But the winds of war sweep everything away. On October 23, 1941 he joins the Army. He is twenty-one years old.

A portrait of Angelo Sirico (on the right) taken in his wedding day

Angelo Sirico (service N. 32543008) is from Ottaviano, on the slopes of the Vesuvius. He was born there in 1921, the son of a timberman, Domenico, who had fought in World War I in the Bersaglieri Corps and had been seriously injured. In June 1921 Domenico emigrates to the United States and at the end of the year his wife and young children Mario and Angelo join him. In Brooklyn, they have five more kids. Angelo, who has a passion for drawing, studies at the Brooklyn High School. In 1942, at agetwenty-one, he is drafted and sent to Europe: on the “enemy” side there were a few relatives of his, who were wearing the Italian Army uniform.

When the information about Angelo being “missing in action”reachestheir home in Brooklyn, Domenico makes no mention ofit to his wife, to protect her from grieving. And does the same when the telegram with news of Angelo’s death is delivered. Anna will die in 1945 without knowing she was thus reuniting with her son.

Alfred L. De Flumeri (service N. 31252071) is the “oldest” of the unit. He was born on May 26, 1911 in Natick, Massachusetts, where his familyhad settled. They were originally from Melito Valle Bonito, today’s Melito Irpino (Avellino province). It is from here that thestory of the De Flumeri immigrants begins: a story that is so similar to thousand others. Alfred’s father Nicola and his mother Angela Maria arrive in the United States at the beginning of the century. They live in New York, then Boston and finally Natick, where they settle in Harrison Street and where their five children are born. Nicola is a mason and will eventually become a foreman in a box factory. Alfred grows up and finds a job, first as an excavator operator in construction yards and then as a laborer in a pipe-fitting company. He marries Ida Lodi, his same age, in 1932. Exactly ten years later, at the age of thirty-one he joins the Army in Pennsylvania. In the official document, drawn for the burial, the widow is recorded as Clara De Flumeri.

Salvatore Di Sclafani (service N. 32297264) should not have been part of the OSS because his plan was to join the Navy with his cousin Salvatore. But Salvatore was not admitted because of health issues, so Salvatore gives up that plan and joins another Corps. Salvatore, whom his friends call “Sammy”, is the son of Paolo Di Sclafani and Carmela Lomino who emigrated to the United States at the beginning of the century setting out from Marineo, near Palermo. Paolo, who had joined his brothers John and Frank, works as a farmer in New Orleans and then as a foreman with a construction company in Manhattan. The couple will have seven children, Salvatore is the second, born January 6, 1916. Paolo becomes an American citizen in 1918 and in 1926 the family moves to Brooklyn, in Ashford Street. Before being drafted, Salvatore works as a polisher. During the war he was awarded the Soldier’s Medal for having saved a fellow soldier who was drowning.

Joseph M Farrell (service N. 31329287) was born in Stamford, Connecticut, on April 17, 1922 from an American father of Italian origin and an Italian mother (Carmela De Mattia of Eboli, Salerno province). The archival documents related to him provided amoving view on another, better known mission that occurred shortly before operation Ginny: Joseph hadparticipated in the Anzio landing on January 22, 1944 and on this shore he earned the “Bronze Arrowhead”, the small arrowhead-shaped device worn on the service ribbon.

The official description is: “It is awarded to denote participation in a combat parachute jump, combat glider landing or helicopter assault landing or amphibious assault landingwhile assigned or attached as a member of an organized force carrying out an assigned tactical mission. A soldier must actually exit the aircraft or watercraft to receive assault credit.Individual assault credit is tied directly to the combat assault credit decision for the unit to which the soldier is attached or assigned at the time of the assault. Should a unit be denied assault, no assault credit will accrue to the individual soldiers of the unit. It is worn on the service and suspension ribbons of the Asiatic-Pacific Campaign, European-Africa-Middle Eastern Campaign, Korean Service Medal, Vietnam Service Medal and Armed Force Expeditionary Medal. Only one arrowhead will be worn on any ribbon”. Before joining the Army in 1942, at age twenty, Joseph is employed by the Home Comfort Insulation.

John J Leone’s (service N. 32577443) father, Emilio, was born in Postiglione, in the Salerno province, in 1893. He emigrated to the United States and found a home in Poughkeepsie NY, at 26 Conklin street. Around 1925, he works in a barbershop located at 189 Main. Together with his wife Carmela De Carlo of Maddaloni, Caserta province, they will have seven children: Carmela, Marie, Peter J., Minnie, John J., Emile and Anthony. John J was born on June 24, 1922, he attends Poughkeepsie High School and joins the Armyon November 2, 1943. He is twenty-one when he writes home from Bastia, Corsica, “Dear Mom and Dad, just a few lines to let you know that I am in the best of health and hope everyone at home is the same. I really miss everyone at home and hope this war will end so I may be able to come and see you all real soon. As I told you in my last letter I am on the island of Corsica. It’s a small island owned by the French.

By the way, Mom, if you receive $100 from the Govt. please save it for me. I got paid but there isn’t any store worth spending it in so I am sending it home through the Govt. Well, I guess there isn’t any more to say so I will close now. Hope to hear from you soon. Love to all. Your son Johnny”. Just a few months later, the mission with no return will set out from that town. We were able to find his 93-year old brother, Emile in an assisted living facility in Crozet, Virginia: “John was three years older than me”- he tells us with emotion- “we shared the same room. He was independent, had lots of friends and lots of girlfriends. He came home late at night almost all the time, 3, even 4 am”.

Another Giuseppe: Joseph A Libardi (service N. 31212732). He was born September 21, 1921 in Stockbridge, Massachusetts. In a picture we found, he is timidly smiling with his gaze directed to something or someone to his left. He is the son of Giuseppe Giocondo Libardi who was born in Levico in 1888 when the town was still under Austrian rule and many people were emigrating to America to escape from misery. He founda job with the Lee Lime Corp., an open pit quarry: an exhausting activity andthe risk of developing silicosis. In 1919, Giuseppe married Rose Merci who had also emigrated from the Trentino region. They will have seven children including Joseph.

A postcard sent by Dominick Mauro to his family

Dominick C. Mauro’s (service N. 32650582) father, Pietro, was born in 1882 in Baucina, 15 miles from Palermo. His mother Biagia Randazzo, from the same town, was born in 1889. They meet in New York, get married and live at 2 Prince Street where Dominick and eight other children were born. There is a church in Brooklyn, founded by the Baucina community and dedicated to Santa Fortunata, Patron Saint of Baucina. After four years of high school, at age twenty-five, in December 1942 he is drafted, just as his other brothers (his brother Saverio will write home from …somewhere in New Guinea). Dominick writes home too: “Dear Mom, don’t know whether this letter will reach you as quickly as I would like. Anyway, the purpose intended is to give you my new address and to remind you of the fact that you will not hear from me for several weeks. This precaution is purely for our protection. … For heaven’s sake don’t worry about the khaki suit I left home. The Army has more clothes than we can use up. Will write you as soon as it is safe to do so. Love to all. Your son Dick”.

Joseph Noia’s (service N. 32536119) family history is another classical story of immigration. Nicola Noia, Joseph’s father, abandons the mountains of San Lorenzo Bellizzi, Cosenza province, in 1912 and travels to Naples where he sails aboard the “Oceania” to reach his father who had already emigrated to New York. He is a blacksmith. He marries Concetta De Simone, originally from Enna. They move from Baltimore to Manhattan. They will have three children. Joseph (1919), Maddalena and Rosalia. In Manhattan they live at 98 118th street. Joseph studies and will eventually work as a playground teacher in a school and attend two years of college. He is drafted in 1942, two years after having suffered the loss of his sixteen-year old sister Rosalia.

Vincent J Russo (service N. 01109637) was born in 1916. His father Giovanni had emigrated from Rocchetta Sant’Antonio, Foggia province, in 1906 on board the “Città di Napoli”, after having prayed to the venerated Madonna of the Well -in town She performed miracles. Giovanni is a construction worker. In 1911, in the Bronx he married Luisa Marano, she too from Rocchetta Sant’Antonio. They settle in Montclair, New Jersey and have five children: Mary Ripalda who will be a saleswoman in a department store, Josephine will find a job as a bookkeeper, Vincent, also a construction worker, John Jr. and Adelina.

We find something out about Thomas N Savino (service N. 32540701) by reaching out to his daughter Grace, now in her mid seventies, who lives in Virginia. She was only one year old when her father was killed. Several years later, her mother Margaret remarried. Thomas’ story was not shared in the family and Grace grew up not knowing much about him. In our research, we were able to find the original text of the “Silver Star Citation” that he was awardedand we immediately sent it to Grace. She told us that her father was originally from the Puglia region. Her grandfather did not speakEnglish but every time they met he would hug her tightly and explain with gestures that she reminded himof his son very much. A picture of Thomas N Savino, Margaret and baby Grace was pulled out of a family drawer.

Rosario F Squatrito (service N. 32542038) is the son of Sicilian immigrants: his father left Monreale in 1902 on board the “Italia” and his mother had left on board the “Neapolitan Prince” a couple of years earlier. They meet in New York, get married and have nine children. Rosario was born in 1922 and has a number of nicknames: Saddo, Sonny and Rosy. He has a strong passion for football and secretly stealshis father’s De Nobili cigars. He finds a job with Superior Die Cutting in Little Italy. He is drafted and decides to join the commandos. His family is totally against this dangerous decision. There is Ann in his life, his girlfriend. The day before he leavesfor training, in tears, she tells Rosario that she hopes that tomorrow never comes.

Training is tough and it includes exercises in water, but that doesn’t worry him because he was born in South Beach. In a letter sent to his girlfriend from Europe he says: “My dearest Ann, I can finally write you. I am on the island of Corsica, a French island. I hope you received my letter from USS Monticello. It is not easy to write lying ina bunkbed on a ship that goes up and down. We had rough seas and several tempests and this is why I could not write much. There was actually not too much to say other than that I love you and that I miss you. But you already know this. Frank Zabatta and I became good friends and were assigned the same room. The place where we are staying is an old hotel called Splendid. Always better than sleeping under a tent like we did in Washington or on a cot of aswinging ship. I gave your name to Frank who will give it to his wife Rose. She will call you and maybe you can go see a show together. You are two Italian girls with strong feelings about the family and same feelings and values. We began our training and I noticed that after three weeks on the ship my muscles are weak. Please share this letter with Mother and Father. Tell them that I miss them and that I love them. I will write you soon. With all the love in my heart, for you and you alone. Be well and God bless us all. Sonny.” Rosario’s mother never wanted to believe that her son had died: the dogtag was not returned and she passed thinking that her son survived and that he was safely somewhere.

On March 7, 1944, Paul J. Traficante (service N. 01308399) writes home from the training camp: “Hello Folks, just a few lines to let you know that all is well and I hope it is the same from home. I received another one of your packages today and this time it was the one with the camera. […] It was very nice of Jimmy and Frances to send me the camera. […] There isn’t much doing here and the grind is getting very boring. We had an American movie here and it was so old it wasn’t even funny. […] What is the news back home? Anything happening? I suppose that the streets around there are getting pretty dead as all the fellows are in the service. Over here all you see are soldiers and more soldiers.” Jimmy is his older brother. e had married Frances in 1941. During their wedding party they were reached by the news of the Pearl Harbor attack: Paul, who had completed his draft assignment, re-enlisted two months later, in March 1942. He is twenty-three. His father Calogero and his mother Accursia emigrated from Caltabellotta near Agrigento. Paul also had twin sisters: Vincenza and Pellegrina.

Liberty J.Tremonte (service N. 31329179). His first name expresses the spirit that inspired him all life long. His father Edoardo had emigrated to the United States from Serino (Avellino); his mother Vita Renzulli from San Michele a Serino. Liberty was born on February 16, 1920 in Westport, Connecticut. He hadfour sisters and four brothers. All of his brothers were inthe military (three during WWII and the youngest, Albert, in Korea). In August 1943, Liberty writes a letter to his sister Carmela: “Hi Sis, maybe it won’t be too long before we see each other again. It’s a very nice place up here, we do lots of exercise that’s the most important part in this outfit. We are called the Gorillas, imagine a little shrimp like me being a gorilla. I’m somewhere in Washington, that’s all I can tell you. This is a very secret outfit. We can hardly say anything.” A “shrimp” who was awarded the “Bronze Arrowhead” during the Anzio landing, just like Farrell.

Livio Vieceli (service N. 33037797).October 1906. In his home in Fonzaso near Belluno where he was born in 1884, Angelo Vieceli is putting his few clothes in a suitcase. He decided to join his brother Giovanni who had emigrated in the United States. The first leg of his journey is through continental Europe: he travels 1300 miles and reaches the Cherbourg harbor, on the northernmost coast of France. He boards the ship together with two thousand “desperate” travelers and reaches the United States after one week. In Manor, Pennsylvania, he marriesAngelina, who had emigrated from Ognano di Conegliano. They have eight children: Frank, Dominic, Delfina, Livio, Louis nicknamed Gino, Celestina. Blanche and Gildo. War sweeps across Europe: four Viecelis enlist, including Blanche, as a nurse with the rank of Captain. Livio was born in 1916, he is drafted from Pennsylvania and becomes a US Army sergeant. In 1944 he is in Europe. He has a family picture with him: 10 people posing in their Sunday’s best, his father looking proud with his mustache and the children looking so much alike. Livio is on the top row on the right.

Paul Traficante

The Mission

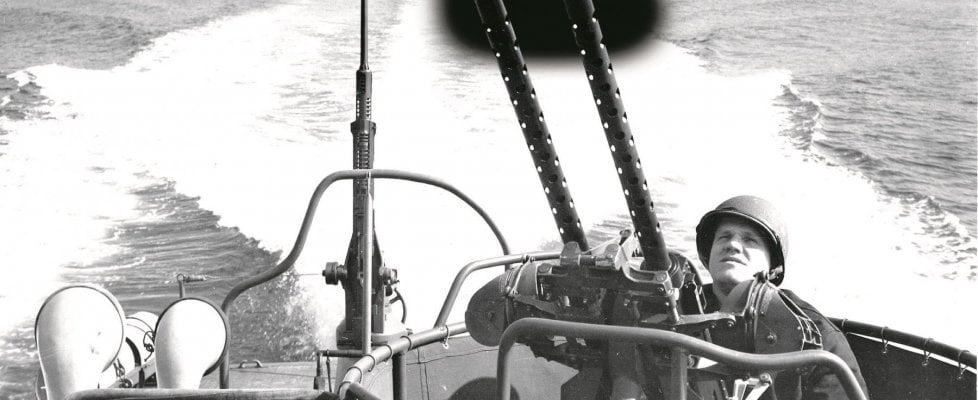

On the evening of March 22, 1944, the 2677 Special Reconnaissance Battalion OSS unit is ready to depart on PT 214 and PT 210, US Navy torpedo boats. The landing site is the coast of Liguria, at a considerable distance, about 170 miles. The commando approaches land west of the Framura railroad station at 11pm, rowing on three rubber boats that had been lowered from the PTs. Once on land, Lt Russo takesthree men and goeson a reconnaissance tour while the others stay on the shore to guard the equipment and the boats. They find out that they had reached Carpeneggio, half way between Bonassola and the Framura station. The target site is about 1.5 miles west. Meanwhile, radio contact with the PT boats is suddenly lost: the PTs had been forced to leave the area asone had detected the presence of German ships and the other had mechanical problems. PT210 is repaired but by then it is dawn and the unit pickup is postponed to the following day.

March 23. The”fifteen” spend the day in hiding, with the rubber boats and explosives tucked away from sight as best they possible could, on the rocky beach. At night, under the cover of darkness, they climb the steep rocky slopes and reach an abandoned stable where they find shelter. They had had no food for twenty-four hours so two of them set out to look for something to eat. A young farmer by the name of Franco Lagaxo, who lives nearby, is the first person to see them. They are close to his home. He provides food for them and takes them to the Framura station, the target of the Ginny mission. That same evening, other PT boats leave Bastia to support the mission. Their assignment is to pick up the “fifteen” but once again, they have to return to base and give up the attempt. On the morning of March 24, a fisherman from nearby Bonassola, who was retuning ashore seesthe rubber boats and informsthe fascist police. Lagaxo tries to alert the Americans but it istoo late: a group of militiamen and German military arrests the commando. Ginny II fails, as another rescue attempt departs from Bastia.

Questioned summarily at the local fascist headquarters, Lt Russo isasked with disdain if he is not ashamed to fight against his father’s native land. Russo does not answer. In those very hours, the Ardeatine Caves massacre takes place in Rome where 335 people were killed as reprisal for a Partisan attack The following interrogations areledby the Nazis at Col. Kurt Almers’ headquarters located in a villa in Carozzo, north of La Spezia. The “fifteen” are taken to the cellar and Kaptanleutnant Georg Sessler, assistant to Korvettenkaptan FrederichKlaps, Chief Intelligence officer, interrogatesthem in his perfect English. He obtains the confession about their sabotage mission, also by means of deception. Sessler returns to La Spezia. Shortly after, the order is given to shoot the captured Americans.

The night between March 25 and 26, the “fifteen” await their execution in a cell in Almers’ headquarters. Oberleutnant Koerbits calls Oberleutnant Bolze, commander of the 1stKompanie of Festungs-Batallion 905 and gives the order to dig a grave that could contain 15 bodies. From Villa Angelo, a property that belonged to a local family in Ameglia, Bolze selects Punta Bianca, a stretch of land along the mouth of the Magra River. On March 26, at dawn the “fifteen” are loaded on trucks. During the ride, a desperate escape attempt fails.

From Punta Bianca you can hear the sea. That was the very last friendly sound that the “fifteen” ever heard. A German doctor arrives on a Topolino car with a red cross painted on the hoodand the prisoners are executed. With their hands tied behind their backs, they are carried to the pit and covered with soil and brushwood and thorns. With mocking delay, the next day, the countermand is sent out: the Americans are not to be executed. Fascist and German radios announce that the American commando was annihilated. To cover up for the execution, they falsely claim that there had been a skirmish where the enemies were killed.

The End

In the meantime, in Bastia there is no news of the “fifteen”: a reconnaissance flight indicates that the tunnel is still intact, so the operation must have failed. A handful of hours later, the radio confirms the feared outcome on “Jerry’s Front Calling”, the counterpropaganda program for the American military in Europe. The sultry voice is Axis Sally’s, an imaginary figure behind which is Italian-American Rita Luisa Zucca. Just as”. Axis Sally lists the names of the “fifteen”, along with the next of kin that appears on the dogtag with the service N. and the city of residence.

On the other side of the Ocean, parents, wives, friends, girlfriends and brothers receive no news: their daily life as immigrants seems to be suspended between their country of origin that has declared war on the United States, and the country that received them. None of the families has been informed that their son, husband, friend, boyfriend, brother ended his life in a mass grave under the shade of trees in Punta Bianca. According to the forensic examinations performed by American medical officers once the mass grave was identified in freed Italy, the fifteen heroes may have been massacred using a shovel: no bullet holes were found on some of the bodies and clothes. An allegation that would require verification, because “rigged” post-mortem examinations, intending to prove torture, were not rare.In a manuscript that we located in the Istituto Ligure per la Storia della Resistenza e dell’Età Contemporanea (Resistance and Contemporary History Institute) in Genoa, partisan Giulio Mongatti, mentions that “an entire commando was massacred by the Germans in the IVth La Spezia zone” and adds that “according to verifications completed by American troops, some of the victims were buried alive”.

Later, the families scattered all over the United States receive mourning telegrams and medals. Sorrow and pride pass on from father to son and end up in a drawer together with faded pictures. Today, the young American descendants of those heroes only bear a last name that links them to a distant Country, and many of them don’t even know who the “fifteen” were. We were the ones who told them their story of so long ago. They know of Private Ryan, not of Alfred, Livio, Angelo and the others, who rest in the Florence American Cemetery, where the white Crosses resemble an army lined up on an emerald green lawn: an unnaturalwar memorial. All died young. Some were buried here. Some returned home in flag-draped coffins. Others ended up somewhere else, like Santoro whom we found in the Mazara del Vallo Municipal Cemetery near the sea: “We have him here!” the cemetery clerk shouted with excitement on the phone at the end of our research. And he went on to say: “Over the years, I could never figure out why this young man in American uniform was here. He rests next to his father”. Lost, forgotten today.

Just like the medals that had been shining during the years of reconquered peace. The “Silver Star” and “Purple Heart” were awarded to all the “fifteen: Sgt De Flumeri, Sgt Vieceli, T/5 Tremonte (also awarded the “Bronze Arrowhead”), T/5 Sirico, T/5 Leone, T/5 Libardi, T/5 Squatrito rest in the Florence American Cemetery; Sgt Noia and Lt Traficante in the Calvary Cemetery in Woodside, NY; Lt Russo in the Immaculate Conception Cemetery of Upper Montclair, NJ, T/5 Mauro in St John’s Cemetery in Middle Village NY, T/5 Calcara in Mazara del Vallo and a park in Detroit is dedicated to him, T/5 Farrell (also awarded the Bronze Arrowhead) in St. Thomas’ Cemetery in Fairfield Connecticut, T/5 Di Sclafani in the Cypress Hills Cemetery, NY, T/5 Savino in the Long Island National Cemetery in East Farmingdale NY.

General Anton Dostler before his execution

The Dostler Trial

The brightness of medals illuminates the fallen for democracy while total darkness swallows the men of absolute evil. Like General Anton Doslter, who had a primary role in the story. In March 1944, he is Commander of the LXXV Army Corps in Italy and is responsible for defending the Ligurian coast in view of Allied landings. These are second line units that have not achieved brilliant military success and Doslter himself is considered sloppy and superficial by his colleagues, more devoted to his lover than to his duties. Previously, he had been a brilliant officer, commanding the 57th Infantry Division in 1941 to conquer the industrial city of Char’kov in Ukraine. He signs the telegram dated March 25, 1944 ordering the killing of the “fifteen”, and a second one confirming the order and rejecting the suspension requests that had arrived from his subordinates. Dostler follows the “Kommandobefehl”, a secret order given by Hitler in 1942 that imposed the immediate elimination of any enemy commando captured in Europe or Africa, even if wearing a uniform. Not carrying out the order meant court martial for the German officer. An order that was totally against the rules of the Geneva Convention on prisoners of war.

For his primary role in the killing of the “fifteen”, Dostler is put on trial and sentenced to death. The trial takes place in Rome, at the Court of Cassation. He is assigned an interpreter, Albert Otto Hirschman, a German Jew who had saved hundreds of persecuted people including Marc Chagall, Max Ernst and Marcel Duchamp.

The Doslter case is somewhat historical because it is considered as the forerunner of the Nuremberg trial. The German General defends himself by saying that he just followed a superior’s order, the “Kommandobefehl”, adding that the murder was ordered by Feldmarshall Albert Kesselring, supreme commander of the German Army in Italy. Kesselring will always deny this reconstruction declaring that he had no knowledge of the capture and killing of the commando. But documents that became available later show that he was in Liguria between March 22 and 25.

Dostler’s sentence established the concept, that will be codified in the “Nuremberg Principles”, that claiming that one was following superior orders is not sufficient to escape punishment. On the other hand, German officer Alexander zu Dohna-Schlobitten, ranking lower that Dostler, had refused to sign the order to shoot the “fifteen” in Punta Bianca and he was only discharged by the Wehrmacht and not sentenced to death by court martial. Dostler was executed in Aversa at 8 am December 1, 1945. He was granted permission to wear the uniform with rank insignia and hat before the firing squad.

Lest We Forget

Historical investigation is largely an invisible activity. Every once in a while, during his work, the researcher resurfaces like a scuba-diver after a long immersion: he is disoriented, has to breathe deeply and gather his energy to be able to describe what he saw. He sits on the deserted beach and gazes at a horizon that differs from the one he had seen before. An endless work that is essential nowadays when memory seems to be fading away, as various facets of fascism, more or less evident, with more or less awareness, are arising. Men and women who lived first-hand those devastating years that were decisive for our freedom will leave us, one at a time, forever. That is when memory becomes precious, so as to not mistake the victims with the perpetrators and to prevent that the border between good and evil disappears like a chalk line blown away by the wind. Over seventy years ago that boundary was very clear, with no ifs or buts. Let’s not forget it and let us retrace it, so that what happened in the “Short Century” will never happen again. “Time grinds and then disperses truth – Nuto Revelli, Italian partisan and writer says- and what is left becomes legend, myth”.

Italian version: “Il plotone perduto”